He’s carried that understanding forward through initiatives like Life Skills Sports Academy, University Little League, and his leadership as Executive Director of the American Red Cross.

Raúl Claros is a man of dreams and realities. Perhaps that’s what led to his decision to run for City Council District 1 (D1) in the June 2, 2026 primary elections.

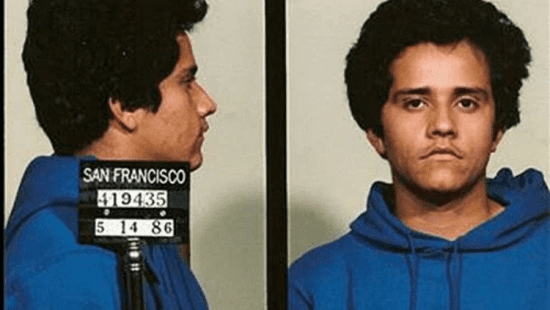

“I’m still that kid who used to run through the streets of Koreatown and Pico-Union, trying to survive in a gang-infested area, getting involved in sports and after-school programs as much as I could to build a future for myself,” says Claros.

He also remembers, at around five years old, going with his father to the stadium to watch the Dodgers play—a passion he would later pass on to his daughter, Valentina.

“We’re three generations who’ve grown up with that tradition. We didn’t have many resources, but I’d sit with my dad in the highest seats in the stadium—it didn’t matter; it was a dream for me. Now, with my daughter, we can sit closer to the field. For me, passing that passion on to her means everything,” he adds.

Unfortunately, neither Claros nor his daughter attends Dodgers games anymore—not for financial reasons, but on principle. Raúl has called for greater clarity and a stronger stance from the Dodgers regarding federal immigration raids carried out in the city.

“My daughter has learned that conviction is something that goes hand in hand with our love for the sport,” he says.

For Raúl, his campaign for city council is simple: District 1 residents deserve a leader who listens and shows up when needed to address community issues.

“What people ask for is very simple: a safer and cleaner community, and to be heard. That’s something the current councilmember, Eunisses Hernández, has failed to deliver. Neighborhood organizations have called me—from places like Pico-Union, Koreatown, even Westlake and Highland Park, which you could say are among her strongest areas. But all I hear is complaint after complaint: ‘She’s not around,’ ‘She doesn’t respond,’ her staff doesn’t know how to solve the community’s needs. The streets are more dangerous, they’re dirty, there’s no street lighting. Residents are living through a crisis, and there’s an absenteeism in her leadership,” he says, motivated.

Claros’s life has been guided by faith, conviction, and some events that seem almost like something out of a movie script.

“My dad is Salvadoran and my mom is from Costa Rica. They met by accident—my mom was in a car crash and it turned out the owner of the car was my dad. That’s how I came into the world. The marriage didn’t work out, but I always felt loved by both of them. I had a very happy childhood,” he adds.

This dual heritage always pushed him to embrace the causes of his parents’ home countries. When he realized there was an (almost) complete lack of Central American politicians, he set out to build a career and become one of the few to represent them in this city. He played a key role in the establishment of the Salvadoran Corridor and has built strong ties with other Central American communities. But he hasn’t stopped there—he also has solid relationships with the Black community in his district.

“We can’t deny who we are or what we represent. Too often, leaders and organizations align with outside interests, forgetting the strength we need as a community. That’s where our power lies—helping make our lives safer. Just look at what MacArthur Park has become: dirty and dangerous. Our parks… I don’t want my daughter playing in a park full of poop or finding needles from drug users. If I don’t want that for my daughter, I don’t want it for the children of D1 either,” he says.

“I’m still that kid walking the streets, full of dreams, fighting for a better life. I just wanted to be a teacher and a coach, and life took me down other paths—without losing my essence.”

Claros credits sports for keeping him away from bad decisions growing up in neighborhoods full of gangs.

“I played baseball and other sports. After school, I’d go to after-school programs. My parents worked all day, and I needed to stay busy with positive activities. I was a left-handed pitcher and a big fan of Fernando Valenzuela,” he recalls.

And maybe, for him, that philosophy applies to this election. When asked what this race means in terms of pitching, he answers with humor:

“Maybe I’d throw a changeup,” he says. “I wasn’t very strong, so I had to use all my tricks to be effective.”

The changeup is an off-speed pitch that pitchers can use to disrupt a hitter’s timing. It usually has some drop or run to the pitcher’s arm side and is typically 6–12 mph slower than a fastball.

He’d leave his opponents swinging.

He graduated with a degree in physical education from Cal State Dominguez Hills, becoming the first in his family to do so. All he ever wanted was to be a teacher his whole life—to teach kids the many ways to enjoy a healthy life.

“However, life gave me other challenges. When I saw all the problems in our community, I decided I had to do something. I worked with Eunisses on the Salvadoran Corridor project, but like other residents, I was disappointed—she stopped showing up to meetings. Street vendors in her district are being hurt with no response from her. Even the Chicanos in Highland Park tell me, ‘Eunisses disappeared, we haven’t seen her,’” he says.

Claros has worked in both state and city offices at various times. He helped form the CD1 Coalition, which, he says, has developed projects that have benefited the community more than the councilmember’s office itself.

“At first, we gave her the benefit of the doubt. ‘She’ll change,’ we told ourselves. But after two years, nothing’s changed. It’s time to take other steps. It’s time for Eunisses to leave office,” he adds.

Claros says one of his main concerns is helping small businesses, as they are the engines of the district’s economy. That money stays in the community, and small businesses have suffered the most under the Trump-era policies.

“Latinos in the district don’t have big malls, movie theaters, or major entertainment venues. We need to support local restaurants and bars so people stay in the neighborhood and have local options,” he says.

There’s a conviction in his voice that sounds strong.

“I believe I can win. I wouldn’t be here if I didn’t. There are a lot of candidates, and I see that as a good thing—it gives us more chances to make it to the runoff. I’m in a solid place with fundraising and the people supporting me. I’m not looking for fame or money. I’m looking for results. My record speaks for itself. At the end of this month, we have the first debate—and I hope Eunisses shows up, so she can hear from the community what I’ve been saying. No group controls me. If something’s good for the community, I’ll work with them. If not, I’ll say thank you and move on. We don’t have much time in this world. I’ll be the Mayor for all the 22 neighborhoods that make up D1. I don’t need to go to training school—I have the experience and the results to prove it.”

And he finishes by repeating:

“I’m still that kid walking the streets, full of dreams, fighting for a better life. I just wanted to be a teacher and a coach, and life took me down other paths—without losing my essence.”