Fear of ICE enforcement is reshaping daily life for immigrant business owners, echoing warning signs long familiar to Latino communities in California

Across Minnesota, a quiet economic slowdown is unfolding—not because of inflation or declining demand, but because of fear.

In recent weeks, small businesses in the Twin Cities, Rochester, and surrounding communities—many of them Latino-owned—have shortened hours, shut down temporarily, or posted signs reading “No ICE.” Owners say the shift follows a visible increase in Immigration and Customs Enforcement activity that has rattled workers and customers alike.

“This isn’t about politics. It’s about whether my employees feel safe enough to come to work,” one Twin Cities restaurant owner told Twin Cities Business, describing staff shortages after reports of nearby immigration arrests circulated through WhatsApp groups and family networks.

A Chilling Effect on Local Economies

Data suggests the fear is not unfounded. According to the American Immigration Council, immigrants make up nearly 18 percent of Minnesota’s small business owners, generating billions in annual revenue statewide. Latino entrepreneurs are especially concentrated in food service, retail, and personal services—industries that rely on daily, in-person labor.

“When enforcement intensifies, the economic impact is immediate,” said Tom K. Wong, a political scientist at UC San Diego who has studied immigration raids and local economies. In previous research published by the Journal of Urban Economics, Wong and colleagues found that workplace raids reduced local employment and consumer spending for months after enforcement actions ended.

Business owners report that ICE activity extends beyond arrests. Several described repeated audits, surprise visits, and requests for employment records that strain small operations with limited legal resources. Even employees with legal status are staying home, worried they could be stopped or questioned simply for being present during an enforcement action.

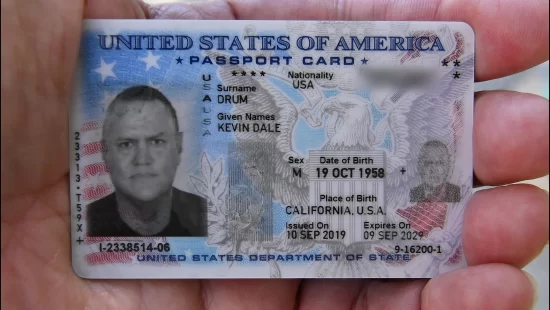

Knowing — and Asserting — Their Rights

In response, some Minnesota businesses have posted signs stating that ICE or Customs and Border Protection officers may not enter private areas without a judicial warrant. Immigration attorneys emphasize that this distinction matters.

“Agents can enter public-facing spaces, like a dining area, but they cannot access kitchens, offices, or back rooms without a judge-signed warrant,” said attorney Iván Espinoza-Madrigal, executive director of Lawyers for Civil Rights, in comments previously shared with NPR. Administrative warrants issued by ICE do not carry the same legal authority.

Still, the legal gray areas leave many owners uneasy. “Even when you know your rights, the power imbalance is real,” one grocery store owner in Rochester told local outlet Post Bulletin. “You don’t want to escalate. You just want everyone to leave safely.”

A Familiar Story for Los Angeles

For Latino communities in Los Angeles, Minnesota’s experience feels painfully familiar. During past ICE surges in LA, entire commercial corridors in Boyle Heights, South LA, and the San Fernando Valley saw foot traffic collapse. A 2019 report by UCLA’s Latino Policy and Politics Institute found that aggressive enforcement reduced small business revenue and weakened trust between communities and local government.

Los Angeles officials later acknowledged that enforcement-heavy approaches hurt tax revenue and slowed post-pandemic recovery in immigrant neighborhoods.

“What we’re seeing in Minnesota now is what California learned the hard way,” said Abel Valenzuela Jr., UCLA professor of urban planning. “Immigration enforcement doesn’t just remove people—it destabilizes local economies.”

For Latino entrepreneurs nationwide, Minnesota’s moment is a warning. When fear enters the workplace, it reshapes behavior, silences communities, and forces business owners into impossible choices.

As one Minnesota bakery owner put it in an interview with MPR News: “Closing early isn’t a protest. It’s the only way I know how to protect my people.”

For many Latino-owned businesses—from Los Angeles to St. Paul—survival now depends not just on customers, but on whether safety can exist alongside enforcement.