After years of confiscating rising amounts of fentanyl, the opioid that has fueled the most lethal drug epidemic in American history, U.S. officials are confronting a new and puzzling reality at the Mexican border.

Fentanyl seizures are plummeting.

After having become one of the main political issues and with the apprehension of the main leaders of the Sinaloa cartel, fentanyl seems to have disappeared from the political scene.

The phenomenon has received little notice in Washington, where the Trump administration has made fentanyl-trafficking cartels a national security priority. “Narcotics of all kinds are pouring across our borders,” he said in a White House statement in March, announcing stiff tariffs on Mexico and Canada.

New data suggest a more complex story. The U.S. government’s average monthly seizures of fentanyl at the Mexican border have dropped by more than half — from 1,700 pounds in 2024, to 746 pounds this year, according to Customs and Border Protection data. The White House says the drop is “thanks to President Trump’s policies empowering law enforcement officials to dismantle drug trafficking networks.” Yet the decline started before Trump took office in January. (While officials only manage to detect part of the fentanyl crossing the border, the figure serves as a proxy for supply).

The contraction represents something of a mystery, say antidrug agents and investigators. Are Mexican cartels producing less fentanyl? Or have they simply found new ways to sneak it across the border? Fentanyl is still cheap and widely available in the United States, according to analysts and drug enforcement agents. Yet overdose deaths plunged nearly 27 percent last year, compared with 2023, according to estimates published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The biggest cause of such deaths are illicit synthetic opioids, especially fentanyl.

Drugs are still killing a harrowing number of Americans — an estimated 80,391 last year. But scientists have rarely seen such a sharp decline in overdose deaths. Interviews with more than a dozen drug-enforcement officers, academics, medical personnel and scientists point to some surprising shifts in the opioid epidemic.

Here’s what’s changing with fentanyl

US seizures at the Mexican border are down almost 30 percent for the first half of this fiscal year, compared with the same period in 2024. They have shrunk by even more since the first half of 2023 — from 13,804 pounds to 6,749 pounds. (Those numbers are for the first six months of each fiscal year, which starts in October).

“One cannot deny there is a big drop,” said Vanda Felbab-Brown, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution who studies the fentanyl crisis. “How long it’s going to last is the critical thing.”

The decline is occurring even as the Trump administration has deployed thousands of troops to the border and expanded drone flights. With more boots on the ground, you’d think seizures would go up — not down.

Some security officials think cartels could be seeking ways to get around border security forces — by mailing the fentanyl, or digging tunnels. After all, there’s still plenty of fentanyl available on U.S. streets. This month, DEA agents confiscated more than 880 pounds of the opioid in a “historic” operation, most of it in Albuquerque. Yet, even including such operations in the U.S. interior, fentanyl seizures have been declining.

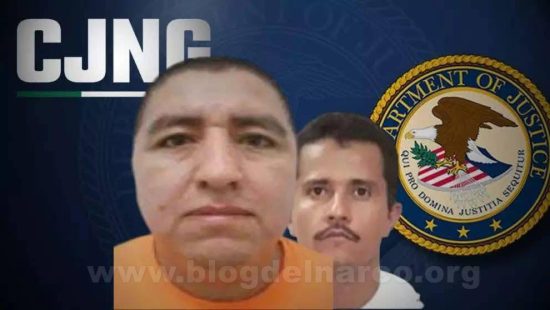

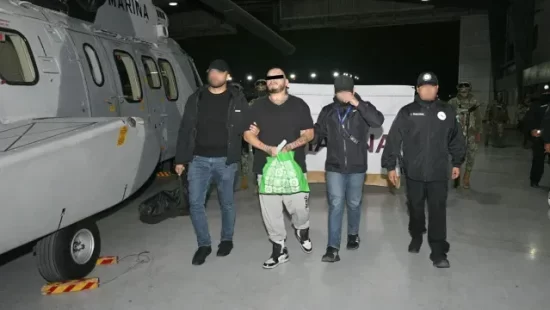

The government of President Claudia Sheinbaum has taken advantage of the turmoil in the cartel to arrest scores of leading members. That may have made it even harder for them to keep up fentanyl production.

The DEA’s annual threat report says there are signs that “many Mexico-based fentanyl cooks are having difficulty obtaining some key precursor chemicals” to make the drug.

US antidrug agents have been trying to outwit precursor suppliers. One program run by Homeland Security Investigations, Operation Hydra, has resulted in the seizure of more than 3.4 million pounds of chemicals.

Maybe the demand for fentanyl is dropping

If less fentanyl is reaching U.S. streets, why isn’t the price going up? It could be that demand has decreased, said Nabarun Dasgupta, an epidemiologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.