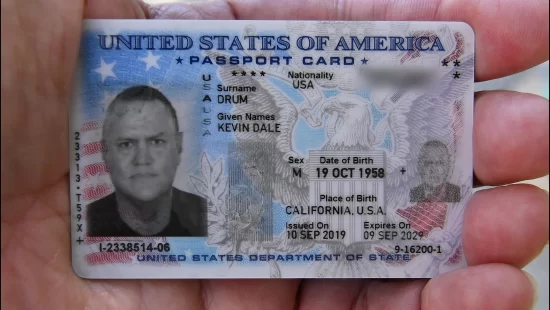

His mother Nicolasa, Hugo, his father Sinar and his wife Lucila.

A few years ago, Hugo Ochoa was just $40,000 away from achieving one of his dreams: a net worth of $1 million. However, bad decisions and market conditions became barriers that prevented him from reaching that goal. Instead, he lost what he had invested and had to start over. This time, though, he already knew where he had failed and what he needed to do—something he had done his entire life.

“I had to make drastic decisions, make better decisions. I already knew what to do in my work. I didn’t see it as a failure—on the contrary, these are experiences that leave us lessons. I reinvented myself, built another company, and grew it. I already knew what had to be done. You can’t sit around waiting by the phone to see if someone calls. You have to go out, talk to builders, look for projects. If you did things right before, the rest comes by default,” says Ochoa, owner of Ochoa Builders, a full-service home construction company that handles everything from A to Z.

Life was not easy for this Salvadoran, born in Santa Ana, El Salvador.

From the age of five or six, he had to wake up around five in the morning to help his father, Sinar, in the agricultural fields, return home at 10 a.m., bathe and eat something, and then walk 40 minutes to get to school.

“We were very poor. We would wake up, and there was coffee; sometimes there was sweet bread, other days nothing. We had to go to work without eating. When that happened, we would get tortillas and eat them with coffee,” says the entrepreneur.

He grew up with five siblings. He liked playing soccer when he had the chance, but he always loved studying from a very young age. He lived in a dirt-floor house and had to place a candle on his chest to be able to read. Nothing was an obstacle to his goals.

“I always saw how hard life was. I don’t complain. I think these are teachings, experiences that life gives us. When I went to school, I didn’t have the right clothes. I remember that one of my old shoes once flew off when I kicked the ball, and everyone laughed at me because my socks were torn. That was my reality. I didn’t take it badly—I hung out with other kids in the same conditions. So I knew I wasn’t alone,” he adds.

One of the things that impacted him the most, even at a young age, was seeing how much his father worked and how little he earned. It felt unfair to him, and he didn’t want that life.

“My dad is one of the hardest-working men I know. I saw how much money he earned and told myself I had to change that. One day I stood in front of him and said, ‘Dad, I don’t want to have your experience. I don’t want to keep working like this my whole life. I want to study.’ He understood and told me, ‘If that’s what you want, I’ll support you. Give it your all.’”

That’s how he was able to continue studying.

“My dad earned $21 a week and gave me $18 for my expenses. I had to pay for school programs and then stay at my uncles’ house. I tried to save some money to give it back to him on the weekend. During recess, I would wait until the end and eat what my classmates left behind. If someone left a pupusa, I’d take it and eat it. If others left their drinks, I’d grab the bottles. That was my diet,” he recalls sadly.

One Thursday, when he arrived at his parents’ house—he usually went on Fridays—he found them sitting at the table eating only tortillas with salt. They told him that all the money they earned was being given to him. Generous as his father was, he compassionately told him, “Tomorrow I get paid; we’ll be able to eat something else.”

“Imagine that—they were left with three dollars a week, and I took eighteen. I thought about it and decided to stop studying; the sacrifice was too much. My dad talked to me and asked me to at least finish high school, since that’s what they had sacrificed for. I agreed and finished it. I was 18 years old, and I had arranged with my older brother, who had already migrated to California, for him to take me with him. He did, and shortly after I found myself in San Bernardino,” he says.

“My dad is one of the hardest-working men I know. I saw how much money he earned and told myself I had to change that.”

Before leaving Santa Ana, he told his father, “Once I start working, you won’t lack anything. I’ll take care of you.”

His brother lived in his uncles’ house. They worked in construction as roofers, and it wasn’t hard for Hugo to start working right away.

“That’s where my path and routine began. My brother and I worked from sunrise to sunset. I only had one thing in mind: work, earn money, and help my family. I had no time for anything else. Monday through Saturday we worked; Sundays we rested and had a barbecue. Then Monday again. I was never interested in alcohol or drugs. Many workers start working and spend all their money on that. Since I was a kid, I dreamed of becoming a millionaire, and between that and helping my parents, I had no other thoughts,” he adds.

“I remember my first paycheck: $280 for the week. I bought clothes and sent $120 to my dad. He was so happy,” he adds.

He worked for a while with his brother and uncle at one company, then moved to another. His brother, like him, was very focused on work. They decided to form their own crew and began looking for more jobs. Things went better—they got more houses under construction, focused entirely on roofing, and because they were fast, they finished quicker and moved on to the next project. Their income increased.

Later, one of the companies closed and he was left without work. He didn’t give up. He went out to construction sites, asking for opportunities, and no one believed in him. One day, he arrived at another site and that’s where his life changed. The man looked at him seriously and asked if he knew how to do roofing. Hugo said that was his strength.

“You’re very young,” the man said, staring at him.

“Just give me the opportunity—I need it,” Hugo replied.

“He tested me for five minutes, liked my work, and started hiring me. Then I got other jobs, brought my brother and a friend, and we were working on several houses, finishing quickly and charging less than others. Little by little, I built relationships, found more work, and built my first company. I began to become independent and reached about 40 houses,” he says.

“I teach my employees that the first thing is to improve as people, not to focus only on wages.”

When the roofing business began to decline, it evolved into a general construction company.

“They would ask me, ‘Do you know how to do this?’ And I’d say, ‘I don’t do it, but I have people who do.’ That’s how the boom started and my first company grew,” he adds.

Then came difficult times—COVID, projects that couldn’t be finished, materials that couldn’t be used, and mounting debt.

“I was $40,000 away from reaching my first million, but it all collapsed. I had to go through that experience to take another path and open Ochoa Builders. I managed to pay off everything I owed. My company closed last year with four million dollars in revenue, and this year I’m projecting five million. What I have now is the fruit of my work. I’ve never failed a client. I learned how to be a boss. I teach my employees that the first thing is to improve as people, not to focus only on wages. If a worker comes to me asking for a job and I ask, ‘How much do you want to earn?’ and they say, ‘It doesn’t matter,’ that will be a good worker. I want them to grow. I don’t want to pass my problems on to them.”

Hugo hasn’t forgotten his family or his community. He has built around ten houses for the community he’s from. He also helps people in need in Santa Ana.

In these uncertain times, Hugo knows the market is far from ideal. The economy is tough, and buying a home is not easy.

“A person with a normal salary can’t buy a house—it’s impossible. You have to earn more than $200,000 a year, because on a one-million-dollar home, the mortgage payment can reach $8,000 a month. Right now, I know how to move. It’s not complicated for me. I go out, look for projects, present plans, and stay in touch with people. That keeps me connected. If I sit around waiting for a phone call, I’m dead—I won’t get work. Right now, I have eight projects, some in the Pacific Palisades area that were affected by the fires,” he says.

Immigration raids have put the construction sector in a vulnerable position. Hugo has taken precautions for that as well.

“We have a plan. I have a full-time worker stationed at a certain distance from our job sites. If he sees any suspicious activity, he has time to warn us. We have an evacuation plan. Safety comes first,” he concludes.

ADVICE

-

Find yourself and understand your purpose.

-

Don’t work only for money, but also to learn. If a job ends, you can find another one using your skills.

-

Daily message: What am I going to learn today?

-

Starting on your own is difficult. You always need clients who pay the bills so you can grow.

-

Don’t try to make a lot of money at the beginning; charge less at first.

-

Everything else will fall into place.